【国际人才交流】与古生物学家一起,穿越时间探索生命

——访中科院古脊椎动物和古人类学研究所教授托马斯·斯坦哈姆

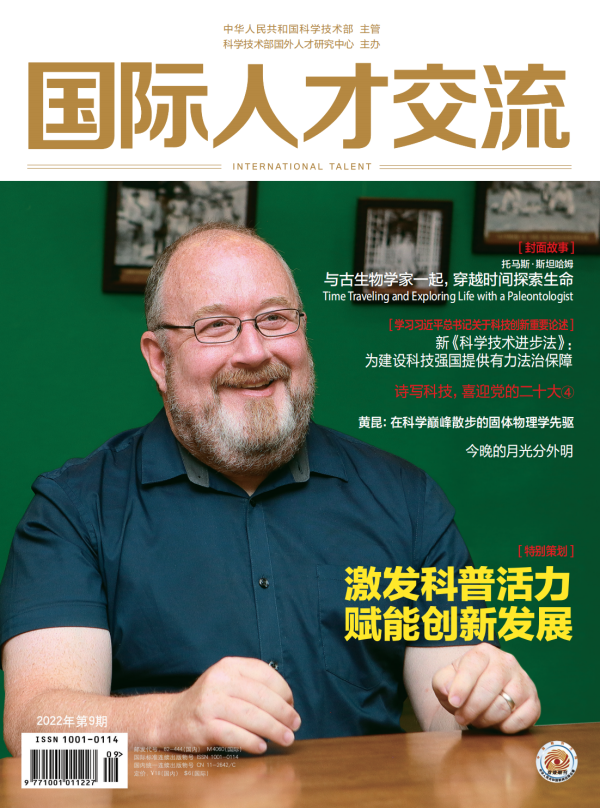

《国际人才交流》封面图

托马斯·斯坦哈姆(美国),获加州大学伯克利分校综合生物学博士学位,并在该校完成博士后研究。他曾在美国得克萨斯A&M大学工作。2012年来到中国,现任中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所教授、中国科学院大学兼职教授。在《自然》《自然通讯》和《美国国家科学院院刊》等期刊上发表约80篇论文。

2022年7月29日晚,在中国古动物馆,中科院古脊椎动物和古人类学研究所(IVPP)教授托马斯·斯坦哈姆(Thomas A. Stidham)以“鸟类——会飞的神奇恐龙”为题,为小朋友们带来了一场生动的科普讲座。他介绍了“鸟类是恐龙后裔”的多种证据,比如它们如何站立行走、相似的骨骼结构和形状、羽毛和蛋的特点,等等。托马斯来自美国,在中国已经工作了10余年,是一位鸟类进化和化石研究方面的知名专家。我们的采访,就约在了中国古动物馆的一间教室。这家博物馆并不大,主要陈列中国各地发现的脊椎动物化石,比如带羽恐龙、早期有颌鱼类、生活在中国的第一批人类等,尤其是由中国人自主发现、发掘、研究的第一条恐龙——许氏禄丰龙,这些化石为我们展示了脊椎动物的进化历程。教室四周的墙上挂满了我国著名地质学家和古生物学家杨钟健的照片,他是我国古脊椎动物学的开拓者,最早刊发了关于许氏禄丰龙的论文。托马斯说,他的研究涉及多门学科,大家可以称他是进化生物学家、古生物学家、鸟类学家、综合生物学家,甚至是动物考古学家。简单来说,他运用各种方法研究来自中国和世界各地的鸟类化石,研究重点是鸟类的进化。短短两个小时的采访,他带领我们走进神奇的古生物世界。

问:古生物学如何引发了您的兴趣,并让您投身其中?

托马斯:我从三岁起就对化石感兴趣,那时父亲给了我人生中的第一本恐龙书,我很快记住了所有恐龙的名字。有趣的是,多年后,我在第一次参加古生物学的专业会议上遇到了这本书的作者,一位已退休多年的科学家。四岁的时候,我开始在学校操场的砾石中收集贝壳,捡化石、捕捉昆虫和蜥蜴、观察岩石这样的事情充满了我的童年。我一直热爱科学,在大学一年级上完第一堂地质学课后,我便从工程专业转到了地质专业。从那时起,因为对科学的热爱、对古生物学的追求,我走遍了世界很多地方,包括北京,也让我有了重大发现,增进了我对脊椎动物特别是鸟类进化的了解。古生物学告诉我们许多不同的事情。化石证明了进化和灭绝的事实,帮助展示我们的历史,让我们知道我们从哪里来,并为我们提供了前进方向的线索。对于古生物学家来说,每一天都在穿越时间,像个探险家一样,发现一个新物种或者揭开一页无人知晓的历史。

问:您是如何来到中国工作的?

托马斯:这是我在中国的第11年了。12年前,我的中国朋友周忠和(原古脊椎动物和古人类学研究所所长)建议我来中国。我们在读研究生的时候就认识了,到现在已经认识25年了。当时我正想调整一下工作,于是我申请来研究所做一年的访问学者。原计划只待一年,结果现在变成了11年,这其中一个重要原因就是我在这里的第一年遇到了我的中国妻子,这改变了我的生活方向;而且我很快就爱上了在北京的研究工作,也很开心和中国同事一起工作。我和中国很有渊源,儿时就梦想来北京参观、认识很多中国古生物学家,还有我的博士后导师、著名古人类学家克拉克·豪威尔是尼克松总统访华后第一批来到中国访问的美国古生物学家之一,他被邀请来中国研究周口店北京人遗址化石,这次来访是中国在化石研究领域开展国际合作的重要转折点。10多年前我刚到北京的时候,研究所做鸟类研究的同事大都在研究辽宁、河北、内蒙古等地发现的热河生物群的早期鸟类化石;相反,我的研究主要关注目前仍存在的一些鸟类的化石,像已灭绝的鸭子、野鸡和猫头鹰。当时中国几乎没有人研究这个方向,我开始建立研究团队。因为,中国有太多的鸟类化石可以研究了。

问:在您发表的论文中有很多鸟类化石的图片,请您介绍一些在中国进行野外实地考察、发现化石的经历。

托马斯:我走过中国的很多地方,做科研或是旅游。例如,我在内蒙古挖掘过恐龙骨骼,在山西农村和新疆偏远地区发现过一些牙齿骨头化石。当然我在世界许多地方都做过实地考察,其实中国大部分的区域都或多或少被考察过了,除了青藏高原、新疆的一些非常偏远的地区。我热爱在世界各地做实地考察。野外工作大多是白天在夏日阳光暴晒下12小时不停歇地仔细观察地面(希望找到牙齿或骨头化石碎片的一丝线索),晚上住在狭窄的帐篷里。但是,发现新化石、发现新化石遗址、与好朋友在一起、在满是星星的天空看到美妙的日出和日落,以及看到野生动物等,会让我忘记这些所有的困难。最令人兴奋的是发现全新的东西。几年前,我和研究所所长邓涛以及几名研究生一起去了山西省榆社县。榆社县以哺乳动物化石闻名。我们选择了一个之前考察不多的区域,岩石层更新一些。我们采集了很多石头,装进大袋子里,背到附近的河边,然后用非常细的筛网冲洗掉数百公斤的沉淀物,以筛选出微小的骨骼和牙齿的化石。在把一块石头放进筛网中时,我突然看到一块破碎的鸟脚骨头从石头里伸出来。简单清理后,我立刻认出它不仅是鸟,而且是鸊鷉——一种会潜水的鸟。中国还没有发表过鸊鷉化石相关的论文,我当时就知道自己发现了一种新的已灭绝的鸟类。这真是太棒了!

问:在中国工作了10余年,您感受如何?

托马斯:中国在许多方面改变了我的生活。中科院古脊椎动物和古人类学研究所是世界上顶级的古脊椎动物研究所,作为一名科学家,在这里我能够不断成长、推进我的研究,我能够与我的中国同事以及世界各地的合作者密切合作。我已与20多名同事合作发表了论文、获得了科研基金。此外,我一直在研究这个世界上一些最神奇的化石。中国拥有大量化石,特别是恐龙、早期鸟类和人类化石。例如,我们刚刚发表了论文,介绍第一个在白天而不是晚上活动的猫头鹰化石,这改变了我们对猫头鹰进化的看法。总的来说,我在这里能一直专注于研究,这在其他地方可能无法做到。此外,我在中科院大学教授《脊椎动物骨骼比较学》课程,我们研究所的所有学生都必须学习这门课程,也有一些来自北京大学和清华大学的学生也来学习这门课程,因为全北京只有我们开设这门课程。虽然我是鸟类专家,但我也非常了解各种脊椎动物的骨骼,比如哺乳动物、鱼类甚至爬行动物。我的同事会给我一堆动物骨骼,让我帮忙分类并确认。我很喜欢这种工作,因为可以一边听音乐,一边通过显微镜观察微小的骨骼来搜索新发现,而不是在电脑前伏案。除了常规教学工作,我还花了大量时间培养学生如何成为科学家,尤其是指导他们把自己的发现写成英文论文。讲好科学故事,这也是一种技能,我努力把它教授给学生们。

问:为什么中国对古生物学研究很重要?

托马斯:中国对古生物学研究很重要有很多原因。其中一个重要原因是中国的科学家,中国有一些优秀的古生物学家和科学家。他们使用尖端技术和最好的方法来研究生命的进化。我们的研究所拥有先进的实验室和设施,如古代DNA实验室、解剖实验室、高效的电脑网络、CT扫描仪和其他设备。同时,中国是世界上研究恐龙的领先地区之一。如果你看看中国的地质历史,中国大部分地区在过去数百万年中都是陆地,而美国则部分被海洋覆盖。所以在中国会有很多陆地化石,很多恐龙,但鲨鱼和鲸鱼的化石很少。在中国发现了很多的化石,提供了大量的证据,证明了恐龙并不是都灭绝了,比如兽脚类恐龙就进化成了我们今天的鸟类。第一个带羽恐龙的化石就来自中国,我们在中国东北发现了很多带羽恐龙的化石。在中国,很多学者从事从恐龙到鸟类进化的研究。2021年我们在《自然通讯》上发表了一篇论文,证明了早期鸟类头骨的许多特征与霸王龙等恐龙相同,但与当今鸟类头骨的结构和功能是不同的。事实上,很多早期鸟类仍然具有许多恐龙的特征。青藏高原也是另一个重要的研究区域。邓涛所长及其团队的工作表明,在200万年前的冰河时期,许多最初在寒冷、干燥的青藏高原生活的动物扩散到了欧洲、亚洲甚至北美。200多万年前,正是全球气候变得更冷、更干旱的时期,这些变化让这些动物扩大他们的居住范围,它们甚至到了北京。青藏高原的隆起如何影响气候变化和亚洲动物的进化,我们对此非常感兴趣。因此,我的研究主要关注青藏高原的鸟类化石,希望能把这个进化的历程描述得更清晰。

问:中国古生物学研究近年来有怎样的进展?

托马斯:在过去的二三十年中,中国在古生物学研究方面发生了巨大的变化。毫无疑问,中国在化石、生命演化研究的许多方面已经成为研究重镇,这一点得到了大家的认同。这得益于全国发现了许多化石遗址,培养了新一代训练有素的科学家,以及在重要研究问题上开展了国际合作。正是这些进展让我在中国的生活和事业蒸蒸日上。中国在脊椎动物进化的许多领域处于领先地位,不断有突破性的发现和论文发表,而且中国古生物学家已经很好地融入了全球学术界。

托马斯在野外进行实地考察

问:您发表了很多关于鸟类化石的科研论文。您是如何根据化石做研究的?

托马斯:一切都是从化石开始的。对于鸟类骨骼化石,首先你需要确定它是哪一块骨头。然后要仔细观察骨骼上的特征,比如肌肉附着处的痕迹、与其他骨骼连接的关节以及任何洞或开口。对于比较完整的头骨或骨骼,我们会进行CT扫描,这样可以获得表面和内部的详细信息。我在世界各地的博物馆看过成千上万的各类鸟类的骨骼,我可以根据骨头的特征来识别某一特定鸟类的身份。由于我研究当今的鸟类群体,我必须将化石与当今世界存在的1万多种鸟类的骨骼以及200多年来已发表的鸟类化石进行比较。在知道了一块化石是哪种鸟类之后,我用许多不同学科的知识来回答关于古代鸟类如何进化、生活和死亡这些问题。例如,我们利用鸟类骨骼中的胶原蛋白、使用稳定同位素技术来分析它们当时吃什么食物。我们可以做到这一点是因为骨骼中的所有东西都来自我们吃的食物和水。你的骨头和牙齿中隐藏着你吃了什么的记录,当然要通过详细的化学分析才能知道。类似的,关于猫头鹰白天行为的发现,涉及许多不同的研究领域,包括收集详细的数据、利用几何学重建猫头鹰眼睛的大小和形状、与数百种鸟类和爬行动物进行比较、对比它在鸟类族谱中的位置,以及研究当今鸟类的行为习惯等。现代古生物学已跨越了传统学科的界限,我们可以使用任何可能的方法来提高我们对生命演化的认识。

问:您认为古生物学研究的意义何在?

托马斯:首先是了解我们这个星球的历史。每一块新化石都可以讲述一个新故事,或者是为已知的世界增加新的更丰富的信息,或者是改变我们之前的认识。简单如一块骨头或者一颗牙齿就可以改变我们对地球历史和演化的看法。化石是对远古历史的唯一直接记录。化石和古生物学激发了人们的想象力。对许多孩子来说,是恐龙和化石为他们打开了科学的大门。在我发表关于第一块来自青藏高原的鸟骨化石的论文之前,科学家们只能推测高原鸟类的历史故事。作为一名鸟类专家,我曾多次前往青藏高原观察鸟,虽然我们知道今天生活在那里的生物,但没有化石我们无法知道它们的历史。这块鸟骨化石来自一种目前在西藏非常普遍的鸭子——麻鸭,这一块化石就证明它们已经在这里生活了数百万年。我专门研究当今鸟类的化石和进化,研究重点是建立鸟类进化谱系,研究鸟类如何应对过去的气候变化。回顾地球的历史,它曾有过比今天更暖或更冷的时期。随着当前全球变暖,我很想了解气候和环境变化如何影响世界各地的鸟类。通过化石记录,我们不仅可以看到过去100年来的气候变化对动物的影响(很多记录显示鸟类分布、饮食和体重发生了变化),还可以观察过去更早的时期,以此了解全球变暖未来可能给当今的动物带来什么影响。通过对来自北极的一些鸟类化石的研究,我证明了在5000万年前气候变暖的情况下,许多鸟类向北移动了数千公里进入北极圈,然后从一个大陆又到另一个大陆。气候变化将给我们和鸟类带来怎样的未来呢?

问:近年来极端天气频发,古生物学的研究对我们如何应对气候变化有怎样的借鉴意义?

托马斯:我们刚刚谈了过去100年间的气候变化。接下来的问题是,未来一百年或一千年会发生什么。化石和岩石记录是回答这个问题的关键。我们可以看到许多物种灭绝发生在上一次冰河时代结束后的变暖时期。在一项研究中,我们试图弄清楚为什么一些大型食肉鸟类灭绝了,另一些却没有。结果是,一种名为teratorns的鸟(陆地上最大的飞鸟),因为它们的食物猛犸象和乳齿象灭绝而灭绝了;加利福尼亚秃鹰仅在加利福尼亚州幸存下来,因为在这里他们还能吃到鲸和海豹等海洋动物。类似的研究和数据可以帮助我们在未来的气候变化中保护鸟类多样性,可以根据历史预测将来会发生什么。我们通过预测一些动物会向哪里迁移来帮助我们做好规划,比如新建或扩建国家公园,或者是制订其他全新的计划。正因如此,我把重点放在对当今鸟类的研究,而不是那些早已灭绝的、有着恐龙般牙齿的早期鸟类。

问:今年7月全国科技活动周期间,您参与“外国专家科学讲堂”项目为青少年做科普讲座,在中国做科普感受如何?

托马斯:除了教授课程外,我还投入了大量精力做科普,包括在古动物馆组织恐龙之旅、公开讲座、恐龙之夜活动。古动物馆馆长王原非常支持我从事恐龙相关的科普活动。此外,我经常在周口店北京人遗址及其博物馆组织家庭科普活动,也在北京周边组织昆虫和鸟类的观察活动。我还走进许多学校,就恐龙、化石、鸟类和其他科学主题演讲,很高兴看到孩子们与化石和动物亲密接触。家长们总是会给我发孩子们的照片或视频,展现他们对昆虫、岩石和大自然日渐浓厚的兴趣,看到科普和教育活动给孩子们带来的这些变化,我很自豪,希望他们能够继续参与,甚至有一天来和我一起工作。我正在利用北京最好的资源来激发下一代中国科学家对科学的兴趣。虽然一本书或一部《侏罗纪公园》会引起孩子们的兴趣,但我相信像我这样的科学家更应该发挥重要作用,向大众传播科学知识,激发他们的科学热情和想象力,并向他们展示如何实现科学梦想。

问:工作之余您喜欢做些什么?

托马斯:首先,我喜欢探索中国这个国家。从爬长城到参加贵州的少数民族节日,我去过中国大部分地区。青藏高原仍然是我最喜欢的地方之一,我一直计划着再次去那里观察鸟类和品味文化。在北京,我经常上烹饪课,学习如何制作传统的中国美食,比如月饼、豆腐和饺子。此外,因为我研究鸟类,所以只要有机会我就会去观鸟。中国有很多种类的鸟类,在过去的几年里,我一直尝试拍摄更多的照片。我对中国的探索还远远没有结束,还有很多东西等待我去发现。在中国生活了这么多年后,当人们问我来自哪里时,我通常回答北京。成年后,这里是我生活最久的地方。在我心里,我觉得自己就是个北京人。(托马斯爱人王颖为采访和本文撰写提供帮助,特此致谢)

Time Traveling and Exploring Life with a Paleontologist?

—Interview with Thomas A. Stidham, a professor at the Institute of Vertebrate

Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Thomas Stidham (United States). He obtained his Ph.D. in integrative biology from the University of California at Berkeley. After graduation, he held a postdoctoral position in the University of California at Berkeley. He worked at Texas A&M University in the USA. He came to China in 2012, and he is a professor of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and an adjunct professor of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences. He has published about 80 papers with many in the leading journals of Nature, Nature Communications, and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

On the evening of July 29, 2022, Thomas A. Stidham, a professor of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Science, gave a lively science lecture to the assembled children and families titled “Birds are Amazing Flying Dinosaurs” at the Paleozoology Museum of China. He surveyed the different lines of evidence demonstrating that birds are the living descendants of dinosaurs. He focused on how they stand and walk, their shared bone structures and shapes, the characteristics of their feathers and eggs, and other body parts.Thomas, from the United States, has worked in China for more than ten years and is a leading expert in the fossil record and evolution of birds worldwide. Our interview with Thomas was in the science classroom for educational activities at the Paleozoology Museum of China. The museum may not be large, and it tells stories of the fossil record of vertebrates from across China. It records the spectacular discoveries of feathered dinosaurs, early jawed fish, the first humans living in China and Beijing, and even Lufengosaurus, the first dinosaur independently discovered, excavated, and studied by Chinese paleontologists. In addition, the classroom walls are covered with photos of Yang Zhongjian, also known as C.C. Young. Yang is perhaps the most famous Chinese geologist and paleontologist. He pioneered Chinese paleontology and helped to found China’s studies in ancient vertebrate evolution, including describing the first Chinese dinosaur, Lufengosaurus.Thomas explains that he pursues many scientific pathways in his research, and he may be called an evolutionary biologist, a paleontologist, an ornithologist, an integrative biologist, or even a zooarcheologist. Despite that seemingly broad approach to science, he focuses his studies on the evolution of birds by examining their fossils from China and around the world. Over our two-hour-long interview, he helped us to dive into the magical world of ancient creatures.

Q:Why are you interested in paleontology, and why have you devoted yourself to it?

Thomas A. Stidham:I’ve been interested in fossils since I was three. My father gave me my first dinosaur book at that age, and I quickly?remembered the names of all of the dinosaurs in that book and others. The funny thing is that I met the long-retired scientist author of that book many years later while attending my first professional paleontology meeting. When I was four, I started collecting fossil shells in the gravel of my school playgrounds, and I picked up fossils, caught insects and lizards, and looked at rocks throughout my childhood. Science was crucial to my life, and my scientific passion has never stopped. After taking my first geology class during my first year of college, I changed my major to geology from engineering. My pursuit of paleontology, and science in general, has since taken me around the world, including Beijing. It has allowed me to make critical discoveries impacting what we know about the evolution of vertebrates, particularly birds. The study of paleontology and the fossil record tells us many different things. Beyond fossils demonstrating the facts of evolution and extinction, they help to show us our?history on this planet, tell us where we came from, and give us clues as to where we might be going. For a paleontologist, every day is traveling through time and being an explorer who can discover a new species or uncover a page of history that no one knew even existed.

Q:How did you come to work in China?

Thomas A. Stidham:This is my 11th year in China. About 12 years ago, a Chinese friend and colleague, Zhou Zhonghe (former IVPP director), suggested I come to China. I have known him for over 25 years since we were graduate students. At that time, I was looking for a change in my career. So, I applied as he suggested and was awarded a one-year visiting position in the IVPP. That year has since become 11, partly because I met my Chinese wife during my first year, radically changing my direction in life, but also because I quickly grew to enjoy my Beijing-based research and work with my Chinese colleagues. I have always had links and dreams related to China. I know many Chinese paleontologists and have wanted to visit Beijing since childhood. My postdoctoral advisor, Clark Howell, was an eminent paleoanthropologist. Clark was part of the first group of American paleontologists invited to Beijing to study fossils from the Zhoukoudian Peking Man site after President Nixon visited China. Their visit nearly 50 years ago in 1975 marks a turning point in international cooperation on studying fossils from China.When I arrived in the IVPP a decade ago, most of the people that study birds here worked on the fantastic fossil skeletons of the early members of bird evolution from the spectacular Jehol Biota found in fossil deposits in Liaoning, Hebei, and Inner Mongolia. However, my focus is mainly on the fossils of living groups of birds, like extinct ducks, pheasants, and owls. At that time, no one was doing what I was doing anywhere in China, and I started to build that research strength in Beijing because there are so many fossil birds in China to study.

Q:You describe and illustrate many bird fossils in your published papers. Please introduce your experience with fieldwork and fossil discovery in China!

Thomas A. Stidham:In China, I have traveled across much of the country for pleasure and research. From digging up dinosaur bones in Inner Mongolia to finding tiny teeth and broken bones in rural Shanxi and remote parts of Xinjiang, I have helped recover thousands of fossils, including new species in our institute. While I’ve found new fossil specimens in China, I have continued to work on bird fossils from around the world. I love doing fieldwork all over the world. However, fieldwork can be seemingly endless days of carefully looking at the ground under a bright summer sun for 12 hours nonstop (hoping for the hint of a fossil tooth or bone fragment). Then there are the rough nights in the same cramped tent. Nevertheless, there is unparalleled excitement in finding new fossils and fossil sites. Not to mention, being with good friends, seeing fantastic sunrises and sunsets with skies full of stars, and watching unique wildlife in remote areas can make one forget all of those hardships.Finding something that no one has ever seen is exciting. I went with Deng Tao, director of IVPP, and several graduate students to Yushe County in Shanxi Province several years ago. Yushe County is well known for its mammal fossils. We explored an area that had not been visited before, where the rocks are a bit geologically younger. We collected heavy bags of rocks with fossils and carried them on our backs to the nearby river. We washed the hundreds of kilograms of sediments through fine screens to capture the tiny fossil bones and teeth as the deposits were washed away. I was pulling the rocks out of the bags to put into the screens and saved one stone from destruction in the screens because I saw a small broken bird foot bone sticking out from the rock. After cleaning it a little with my finger, I recognized it instantly as a bird bone and a bone from a diving bird called a grebe. There are no published papers on fossil grebes (yet) from China, and I knew then that I had just found a new extinct bird species. It was amazing!

Q:How do you feel about working in China after more than ten years?

Thomas A. Stidham:China changed my life in many ways. IVPP is the top institute for vertebrate paleontology in the world. As a scientist, I have grown and developed my research. I’ve been able to work closely with my Chinese colleagues, as well as with student and professional collaborators around the world. The institute is filled with great colleagues, students, and friends, and I’ve published papers or obtained research grants with more than 20 of my colleagues. In addition, I have worked on some of the most fantastic fossils in the world. China has many spectacular fossils, particularly dinosaurs, early birds, and humans. For example, we just published a paper on the first fossil owl active during the day, not at night, and that single fossil skeleton has changed our view of owl evolution. Overall, I’ve been able to focus on and develop my research in ways I wouldn’t have been able to elsewhere.I have taught our comparative vertebrate osteology course at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences for a decade with a few other faculty members. All students in our institute have to take that class. We even get some students from Peking University and Tsinghua University because we offer the only vertebrate osteology class in Beijing. Though I’m an expert on birds, I know very well the skeletons of most groups of vertebrates, like mammals, fish, and even reptiles. Word of my knowledge has spread, and many of my colleagues will give me their unidentified and random fossil bones, asking me to sort through and identify them. I enjoy that kind of work, not on the computer where I can listen to music, stare through the microscope at tiny bones, and make endless discoveries. In addition to formally teaching students in the classroom, I spend a lot of time working with our students to train them to be professional scientists, in particular by helping them to write and publish their papers on their brilliant discoveries in English. Telling fantastic science stories is a skill I try to pass on to our students.

Q:Why is China important to the study of paleontology?

Thomas A. Stidham:There are many reasons why China is crucial. One of those reasons is the people. We have some excellent paleontologists and scientists here. They use cutting-edge equipment and the best analyses, techniques, and methods to study the evolution of life. Our institute also has some of the best facilities in the world, with multiple CT scanners, an ancient DNA lab, an anatomy lab, a great computer network, and other scientific equipment.China is one of the top places in the world to study dinosaurs and other kinds of animals. If you look at the geological history of China, much of China’s land has existed over many millions of years of geological history. By contrast, America was covered partially by various oceans and seaways during large parts of geological time. As a result, in China, you get more fossils of animals that live on land, like dinosaurs, but very few fossils of sharks or whales. China also provides some of the best fossil materials and key proof to show that not all dinosaurs are extinct; birds evolved from one group of dinosaurs, called theropod dinosaurs. The first fossils of feathered dinosaurs were found in China, and we have discovered many new large and small species of feather dinosaurs in northeastern China. Many people study the evolutionary transition from dinosaurs to birds in China. For example, we published a paper in Nature Communications last year describing our discovery that many features of early bird skulls are shared with dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex and differ from the structure and function of living bird skulls. However, many of these early birds retained many features of their dinosaur ancestors.The Tibetan Plateau is another significant area for research. Deng Tao and his group’s work has shown that during the ice ages over the last 2 million years, many groups of animals that first evolved on the cold and dry Tibetan Plateau spread out of Tibet into the cold and arid habitats of ice age across Europe and Asia, with some even immigrating to North America. The change to a more challenging and drier global climate more than 2 million years ago allowed these animals to expand their ranges over large areas, including Beijing. We are very interested in understanding the role of the rise of the Tibetan Plateau on climate change and the evolution of animals across Asia. I am trying to fill in the part of that story with my studies concerning the fossil record of birds from the plateau.

Q:What recent progress do you see in paleontological research in China?

Thomas A. Stidham:In the last 20 to 30 years, many significant changes have taken place in China related to the study of paleontology. Indeed, the recognition of China as a center of excellence for studying many aspects of the fossil record and the evolution of life has increased significantly. That increase results from many amazing fossil site discoveries across the country, the development of a new generation of well-trained scientists, and international cooperation on essential questions in evolution. Those qualities have led me to a life and career in China. As a result, China is leading the study of many areas of vertebrate evolution with ongoing groundbreaking discoveries and publications, and its paleontologists are well-integrated into global research circles.

Q:You have published many scientific papers on bird fossils. How do you study fossils?

Thomas A. Stidham:Everything starts with the fossil specimen. For a bird bone fossil, first, you need to determine which bone of the skeleton it is. Then, you have to look in detail at the features on the bone, like scars from where muscles are attached, articulations with other bones, and any natural holes or openings. For more complete skulls or skeletons, we will CT-scan the fossils to get detailed information on the surface of the bones and what we usually cannot see inside bones and skulls. As an expert who has looked at thousands of bird skeletons of all groups of birds in museums around the world, I know how to use the features of the bones to exclude some groups as potential identifications. I also know how to obtain the evidence I need to support the best identification of a particular group or species of birds. Since I work on living groups of birds and birds flying everywhere in the world, workers like me have to compare fossils to skeletons of the over 10,000 species of living birds around the world and over 200 years of published fossil birds. After we know what kind of bird the fossil belongs to, I use many different fields of science to answer questions about how ancient birds evolved, lived, and died. For example, we used fossilized stable isotopes of several atomic elements found in the collagen proteins preserved in some bird bones to help reconstruct what long-dead birds ate. We can do that because everything in your bones starts as food and water through your mouth. Your bones and teeth keep a hidden record of what you eat that can only be read with detailed chemical analysis. Similarly, our project examining the oldest record of daytime behavior in owls involved several different lines of study, from gathering precise measurements and using geometry to reconstruct the size and shape of the eye in a fossil owl and comparing it to hundreds of species of birds and reptiles to examining the day and night behaviors across living birds in comparison to their placement in the bird family tree. Old traditional boundaries do not restrict modern paleontology among the sciences, but we use appropriate methods to improve our knowledge of past life.

Q:What do you think is the meaning or impact of paleontological research?

Thomas A. Stidham:Firstly, I think paleontology allows us to know our history on this planet. Every discovery, or new fossil, can either add something to that story or it can change everything about what we thought we knew. It can take as little as one bone or tooth to completely change our view of Earth’s history and evolution. Fossils and the rocks they are found in are the only direct record of what happened in the deep past. Fossils and paleontology light the imagination of people around the world. For many children, dinosaurs and fossils are their introductions to science.Before I published the first fossil bone of a bird from the Tibetan Plateau, scientists could only speculate about the story of birds on the plateau. As a bird specialist, I have gone to the Tibetan Plateau many times to watch living birds, and while we can see what lives there today, we have no idea what their history is without fossils. So it happens that the fossil from the Tibetan Plateau that I reported is from a group of ducks called a shelduck, and that type of duck is quite common across the Tibetan region today. So this single bone fossil helps to show that they have lived there for millions of years and are not recent arrivals.As I’ve said, I specialize in the evolution and fossil record of the living group of birds. My research focuses on building the family tree of birds as a document of their evolution and studying how birds have responded to past climate change. If we look at the history of the Earth, we can see periods when it was warmer or colder than today. With current global warming, I am interested in understanding how climate and environmental change impact birds worldwide and over time. Instead of just seeing the impact of climate change on animals over the last 100 years (with many documented changes to bird distributions, diets, and body masses), the fossil record allows us to look over much more extended periods and potentially see what the future global warming may bring to the animals alive today. For example, in my study of some fossil birds from the Arctic, I showed that with a warming climate 50 million years ago, different groups of birds moved thousands of kilometers further north into the Arctic Circle, which then spread from one continent to another. So what future does climate change have in store for birds and us?

Q:In recent years, extreme weather has occurred frequently. How does paleontological research help in dealing with future climate change?

Thomas A. Stidham:We just talked about the last 100 years of climate change. The natural question is what will happen in the next hundred or thousand years. The fossil and rock records are crucial to answering that question. We can see many extinctions during the last significant warming event after the end of the last ice age. In one of my studies, we tried to figure out why some large carnivorous birds became extinct, and others didn’t. Our analyses showed that one extinct group of birds called teratorns (giant flying birds on land) ate dead mammoths and mastodons (which became extinct, too). The endangered California Condor ate many of the same animals across North America. Teratorns became extinct because their food became extinct. However, the California Condor survived the extinction event only in California, where it was able to eat meat from marine animals like dead whales and seals. Data like those and from other studies on birds can help us plan to conserve bird diversity in the future of climate change by using what happened in the past to predict what will happen soon. We can predict where species should move, and that knowledge can help us to plan for conservation work to protect biological diversity, like building new national parks, expanding existing ones, or developing plans we haven’t?even thought of yet. This kind of research and broader impact is why I focus on the living groups of birds, not the long-extinct, early-toothed dinosaur-like birds.

Q:In July this year, you participated in the Foreign Experts “Science Classes” project during the National Science and Technology Week and gave a science lecture to young people. How do you feel about doing science outreach in China?

Thomas A. Stidham:Beyond my teaching and effort to train future scientists in China, I’ve put in a lot of effort to promote engagement with science and science careers in Beijing. This work includes developing, organizing, and leading many “dinosaur expert” tours for students and families, public talks, and a family overnight dinosaur program in the museum. The museum director, Wang Yuan, has supported my dinosaur outreach activities. In addition, I frequently run a popular family activity and tour at the UNESCO Zhoukoudian “Peking Man” Site and Museum and other insect and bird field experiences around Beijing. I also have visited many school classrooms across Beijing, giving talks and running activities about dinosaurs, fossils, birds, insects, and other science topics. Seeing the excited children engaging with the fossils and animals I love is great. I also am proud to see the long-term impact of my educational programs as parents continue to send me photos or videos of their children months later showing their ongoing discoveries and interests in insects, rocks, and nature, as well as their wish to join my next program or even coming to work with me someday. I am using the best resources in Beijing to light the imagination and interest in science among the next generation of scientists. While a book or a Jurassic Park movie might garner a child’s interest for a moment, I believe that active research scientists like myself need to play a significant role in communicating not only our knowledge of science but also our passion for science to capture the imagination of the public and show them how to make their science daydreams a reality.

Q:What do you like to do in China when you are not working?

Thomas A. Stidham:First, I enjoy exploring the country. From hiking the Great Wall to visiting minority festivals in far-flung places like rural Guizhou, I have seen most parts of China during my time here. The Tibetan Plateau is one of my favorite places in the world, and I’m always planning to return for its rich bird life and culture. In Beijing, I also frequently take cooking classes, learning to make traditional Chinese dishes from scratch, like mooncakes, noodles, tofu, and dumplings. Additionally, since I study birds, I try to watch birds whenever I can. China and Beijing have many species of birds, and I have been trying to take more pictures of them in the last few years. I am far from done exploring China, and I think there is so much left to discover. After being a part of China for so long, I will typically answer Beijing when people ask me where I am from. I have lived here longer than any other place in my adult life, and in my heart, I feel I am a Beijinger now.

(文、译/张晓)